Susan Talalay presented her award to Bambang Harymurti after being introduced by Alfred Friendly Press Partners President Randy Smith

Bambang Harymurti said he never had a chance to meet Alfred Friendly, who died three years before the Indonesian journalist joined the family’s fellowship program in 1986, “but he changed my life forever, and for the better.”

When he left for the United States three decades ago, Harymurti was a 29-year-old reporter for Tempo, covering regional and international news. The weekly magazine was known for its investigative reporting within Indonesia, a country just 20 years into its independence and led by a brutal and corrupt dictatorship.

During his six-month fellowship, Harymurti worked at Time magazine’s Washington bureau, an experience “that was like being transported by a time machine to the future, maybe by a half a century,” he told the audience.

Harymurti was presented the Susan Talalay Award for Outstanding Journalism during a benefit gala at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C., on Sept. 7.

Talalay, a former director of Alfred Friendly Press Partners and board member of the Alfred Friendly Foundation, said Harymurti, initially trained in electrical engineering, “made himself indispensable to the bureau by reconfiguring the bureau’s computer system.”

He went on to write a story about AIDS that made the cover of the magazine, “which was no small feat for a Friendly Fellow, let alone a veteran reporter at Time.”

Harymurti said Alfred Friendly believed that a healthy democracy needed a free press and competent journalists, and that a professional fellowship “is the best education for any journalist. Having participated in this fellowship, he converted me to this belief.”

But the Indonesia he returned to in 1986 was still a place where President Suharto “controlled the masses by instilling a fear of too much freedom.” In 1994, the regime banned Tempo. A few hundred people protested in the streets and were “brutally suppressed.”

Harymurti rose in the ranks of Tempo as Suharto’s regime began to wane. In 1998, Suharto was forced to resign amid widespread rioting and political chaos. “People no longer tolerated dictatorship,” he said.

Tempo reopened, and as the magazine faced court battles and mob attacks during the transition, Harymurti learned that advocating for press freedom and a vibrant democracy “requires resources, time, energy and patience — extraordinary patience, and grit.

“The effort is not just needed when a democracy is emerging, but also when it is under attack, especially by demagogues who are masters in creating false hope,” Harymurti said. “We have to do what we can to stop this. This is one of the main reasons we are gathering here tonight: to ensure freedom prevails so our children will inherit a better way, a free way.”

Talalay, as she presented her award, said Harymurti continues to be “an ardent advocate of freedom of expression and clean government,” even in semi-retirement.

Harymurti is now commissioner of the company that publishes Tempo and other publications in Indonesia, co-founder of the Indonesian Transparency Society that developed the country’s anti-corruption law. He was assigned as a UNESCO international expert in assisting newly democratic countries and is currently involved in a similar role at the Institute for Peace and Democracy, working in Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam and Myanmar.

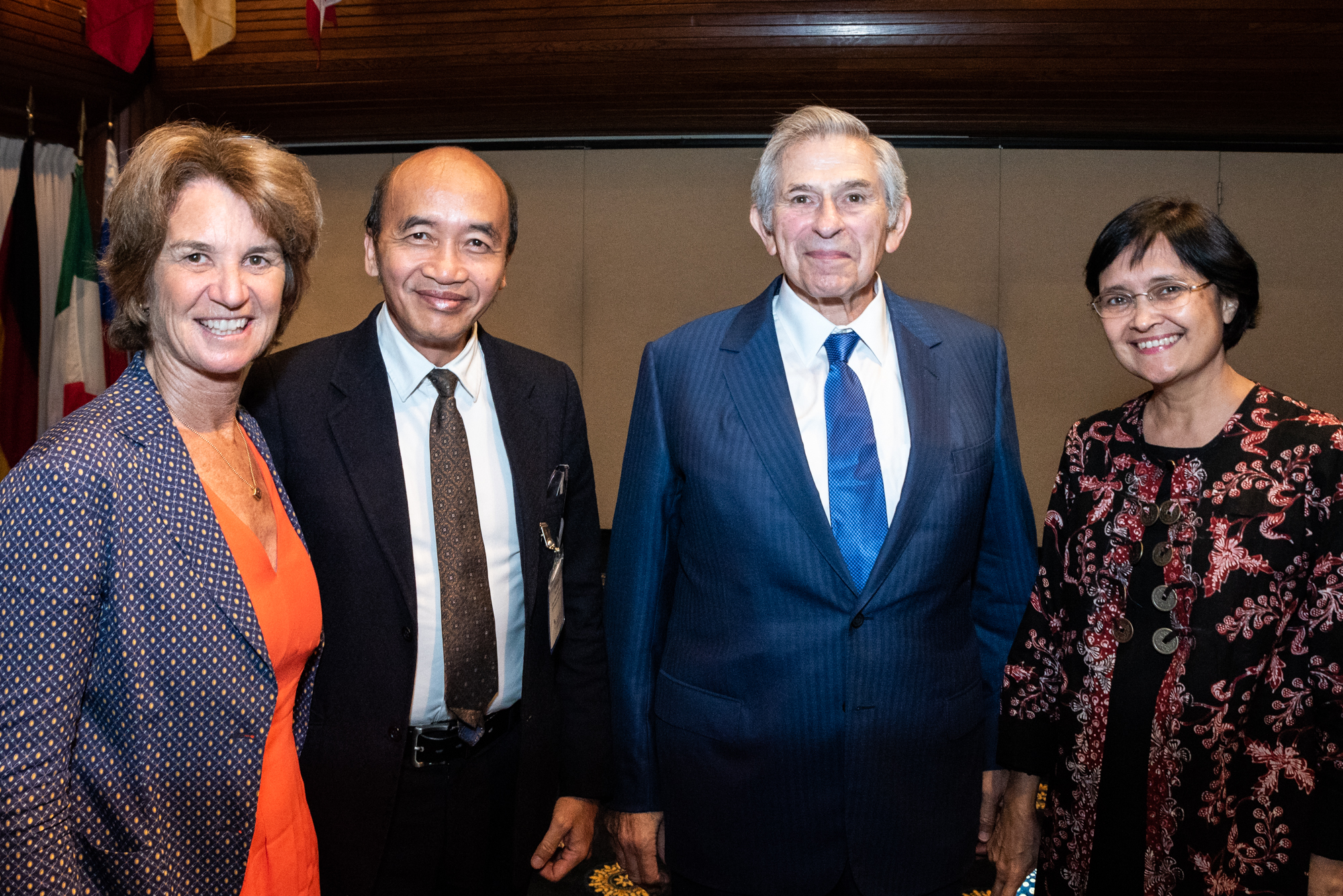

At the gala, Paul Wolfowitz, a former deputy defense secretary, World Bank president and ambassador to Indonesia, reunited with his longtime friend and posed with Bambang, his wife, Marga (right) and Kathleen Kennedy Townsend

After the gala, Harymurti went to the Missouri School of Journalism and spoke to students, faculty and staff at Reynolds Journalism Institute, where the fellowship program is based.