Raised in a cotton-growing region of central India, Jaideep Hardikar has focused much of his 25-year reporting career on farmers and their increasingly perilous livelihood.

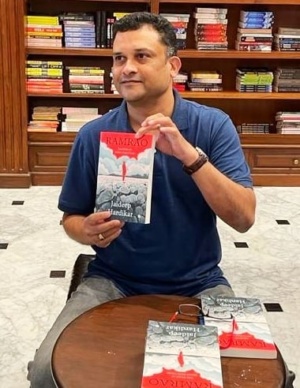

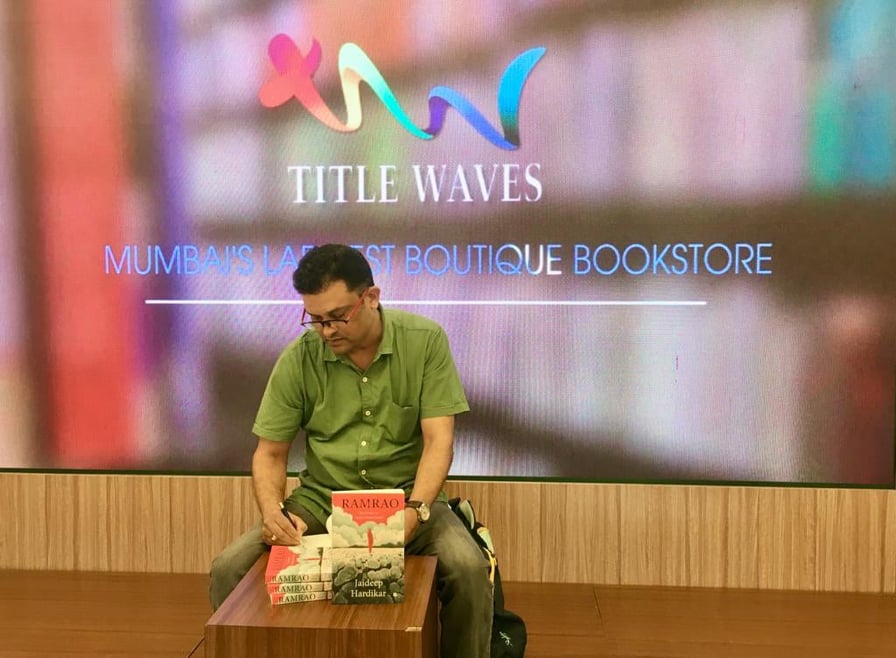

In September, HarperCollins published Hardikar’s second book about India’s agricultural system: “Ramrao, The Story of India’s Farm Crisis.”

The book received glowing reviews, including one by the Hindustan Times that said Hardikar “tells us what it is like to be – financially, socially, emotionally and mentally – an Indian farmer today… The result of years of committed reportage, Ramrao turns an ordinary life into an essential biography for our times.”

As India’s economy liberalized and globalized, Hardikar writes, farmers saw production costs multiply and the cost of living rise while real incomes stagnated. Some farmers protested, and many others committed suicide.

In April 2014, Hardikar went to Maharashtra’s Vidarbha region to interview a desperate cotton farmer named Ramrao Panchleniwar, who had tried to commit suicide by drinking two bottles of insecticide but was saved.

In this condensed conversation with Alfred Friendly Program Director David Reed, Hardikar talked about Ramrao, the book, and the impact of his Alfred Friendly fellowship in 2009, when he trained at Poynter Institute and worked at the South Florida Sun-Sentinel. [Click here for a video version of the interview)

Hardikar:

I really wanted to tell the story of this crisis to an audience that might not necessarily understand the complexities of the issue. I am trying to help them understand how people survive and live with a crisis of this proportion.

More than 400,000 farmers committed suicide in India between 1996 and 2018. Every 30 minutes in India, one farmer commits suicide and ends up as a mere statistic.

It was only in 2016 or 2017 that I began to think that I need to follow Ramrao for more years and see if I could tell his story, and through him the crisis in farming. He is an average farmer who symbolizes India’s farming community.

Reed: What are a few actions the government and society could take to improve the situation?

Hardikar: There are no simplistic solutions. It’s a complicated and complex issue. But if you ask me two or three things that we need to do, we need to augment incomes phenomenally because right now it’s not even subsistence levels that they are at. And we need to structurally see what we can do with our poor farming conditions, which means we need to invest more, not necessarily in big projects, but we need to invest in the rural economy in a way that augments income standards.

Reed: In what ways did the Alfred Friendly Fellowship experience have an impact on your career?

Hardikar: Those six months in the U.S. and at the Sun-Sentinel were a game-changer, a life-changer. My whole perception changed. I worked alongside very good reporters at the Sun-Sentinel and met a lot of good journalists from many parts of the United States. I‘ve learned from them and stayed in touch with them. I don’t look at events, I now look at processes. The idea of a book or the very fact that a journalist could graduate from a 1,000-word story into a more substantial contribution in terms of length, in terms of scale and time — that came during those six months. They were invaluable. Some of those moments are still with me, very alive.