By Asma Ghribi

Seemingly every week brings the story of another newspaper or journalistic magazine laying off staff, ending its print edition, or simply closing up shop. Editors of the Wall Street Journal have found their way through the crisis. As one of them put it, “If you’re interested in the content, you should pay for it.”

If only it were so simple.

The fact that the so-called “hard pay wall” model has worked for the Wall Street Journal doesn’t mean it can work for other outlets. The Journal’s subscriber base includes corporations and investors who need its financial information and will always be willing to pay.

That’s not the case for other papers, even giants such as the New York Times: most of its readers are normal people who may love the content but who won’t be as loyal as the Journal subscribers.

Other skeptics of the pay wall point out that it goes against the fundamental principle of Internet culture: free, instant, global access to information

Moreover, a simple Google search of “New York Times pay wall” reveals several ways to get around that pay wall.

Other outlets have taken a more innovative approach to the challenge of the Internet: if revenue streams are changing, then one’s editorial approach should change to meet it.

Sites like Buzzfeed, HuffPo, and, in a slightly different approach, Vice Magazine, have tailored their approaches to consumers who are hungry for fast, sharable content. Those outlets chose to draw more attention and have managed to survive on ad revenues. Their content is more accessible – both in cost (free) and linguistic tone (simple). As a result, their bases are much larger than the Journal or the Times, who tend to target a more elite audience.

But is this what we want? These Media 2.0 outlets are surviving because they decided they are not going to abide by the same standards as the Times or the Journal. They go for sensational stories, use catchy or shocking (but not always so accurate) titles, and have generally lower standards.

These outlets have figured out how to survive — but it seems to be at the expense of the quality that motivated me to get into journalism in the first place. Isn’t journalism about holding government accountable? Protecting the public interest? Asking difficult questions?

Some would counter that media doesn’t need to be one or the other. In the early 20th century, “yellow journalism” and serious reporting existed side by side.

The problem today is that while sensational media thrives, the other model struggles. In the 1920s and 1930s responsible, investigative journalism was profitable. Now, if you want to succeed and have higher standards you have to starve.

I wish I had an answer for this problem. I wish that one of these models – the Journal’s hard pay wall, the Time’s article limit, or even HuffPo’s catchy headlines– could provide the revenue necessary to employ a healthy corps of ambitious journalists fighting for the public good.

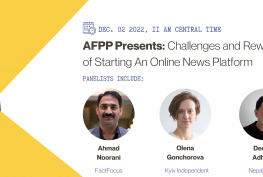

For now, those of us who aspire to do that must be as open and flexible as the editors and publishers who are trying to find a solution themselves. This does not only mean being open to freelancing for low fees, and taking journalism jobs that might not involve the kind of hard reporting we’ve aspired to, but also opting for new ways of gathering information, new techniques, and new possibilities.