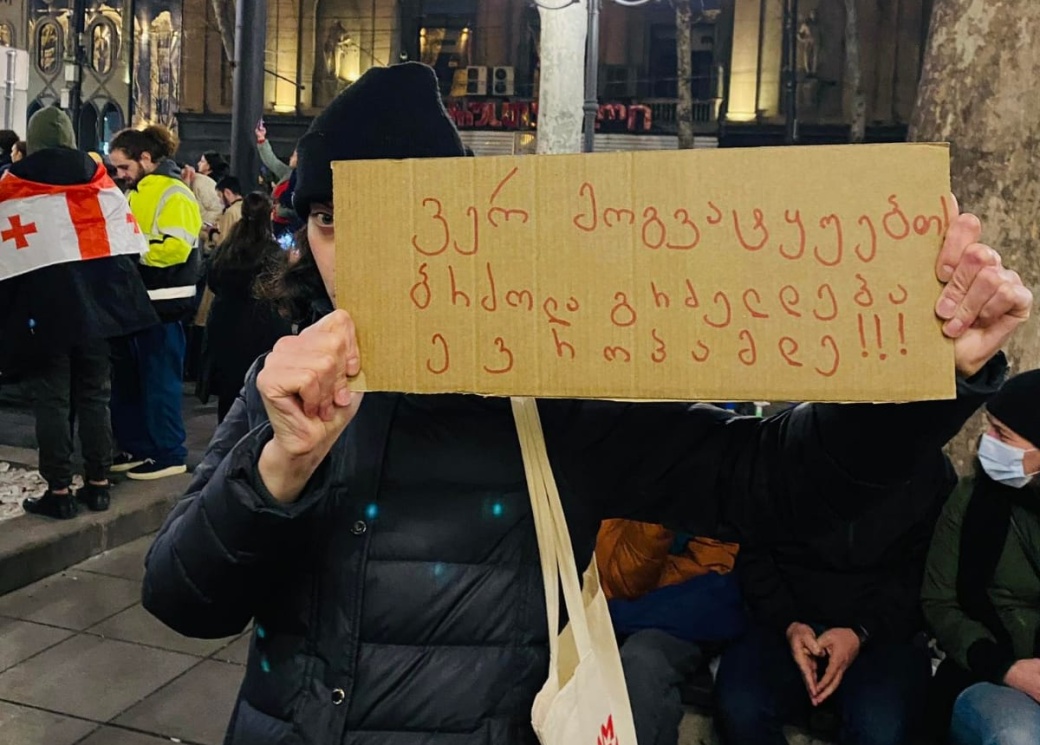

Protesters block Rustaveli Avenue outside Georgia’s parliament building in March

By Khatia Shamanauri, Alfred Friendly Class of 2020

Exactly a year ago, in a local Welsh pub in Cardiff, a friend of my housemate asked me a seemingly harmless question: “Which Georgia are you from – American Georgia, or Russian Georgia?”

This person, I realize now, could not imagine that associating us with our nemesis neighbor could rouse anger and protest in anyone. But still.

“Seriously, Russian Georgia?” I asked back. He seemed surprised, but didn’t step back and repeated again, “Yes, Russian.”

This exchange enraged me so much that I kept telling it to my foreign friends, expressing concern about how someone dared to mention the word “Russian” when referring to my country. Although some of them shared my attitude, many didn’t understand why it was so emotional for me.

The massive, successful street protests in Georgia this week clearly demonstrated to the entire world how most Georgians react to anything that starts with the word “Russian”, be it an influence, a draft law, propaganda or war.

Khatia during her fellowship, 2020

This time, Georgians were protesting the ruling party’s decision to back a Russian-style draft law. It would require non-government organizations and independent media outlets that receive more than 20 percent of their funding from outside Georgia to register as “foreign agents.” Otherwise, they would face huge fines and even imprisonment.

The move was met with widespread condemnation from Georgia’s western partners, who asserted that the law is not compatible with the European Union standards and values and would negatively affect the country’s chances of joining the EU.

By distancing itself from Europe, Georgia could end up in Russia’s orbit. But the sense among Georgians is that we will never accept a return to our dark Soviet past. Through centuries, this sense of independence has never changed. Perhaps it is what brought a small country with fewer than four million residents to become, and remain, a sovereign nation.

Rustaveli Avenue in central Tbilisi, where thousands gathered against the Russian-style law, has long been the epicenter of massive protests. I can’t recall how many times I’ve stood there — sometimes to defend the downtrodden, sometimes to protest the government’s policy or a particular decision. But the spirit of demonstrations against Russian influence is easily recognizable and they always stand out. The scale of anti-Russian protests in Georgia is always remarkable. No matter how large and heavy is the cloud of tear gas that settles over the main avenue, people are always determined to remain there until the final victory is achieved.

Each protest banner tells a unique story. These days, you could see women holding banners that said they were there for their children’s bright future. “Lui, I’m here. You should remember where your mom stood! For freedom!”

Some young people asked a rhetorical question: Why are Georgians supposed to go to Moscow when people travel to Mars in the modern world?

Banners of introverts complained that they were forced to stand with a bunch of strangers due to the dire situation facing Georgia.

The protestor’s sign says: “You can’t lie to us! We will continue the fight until Europe!”

A sign referring to a currently occupied region of Georgia was one of many that caught my eye: “In 1992 my parents fled Abkhazia and came to Ukraine. Russia ruined their lives twice.”

Another sign from a Russian citizen who fled the country after the Ukraine war: “I am from Russia and this is what I escaped from. Fight!”

Indeed, Georgians were determined to fight, and it took only two days until victory was achieved. After the second restless night, disappointed that I was sick and had to stay home, I woke up to the news that the ruling party withdrew the draft law.

This marks the latest victory for the Georgian people, but nobody has the illusion that there will be no more obstacles. Moreover, everyone here will tell you that despite wars, annexation and occupation throughout its history, Georgia has never been a part of Russia. Culturally, it has always belonged to the European family and this will never change.

Khatia Shamanauri, center with Ukrainian-blue hair dye, participates in one of many protests in central Tbilisi