Here’s something I would never thought I’d say. I don’t have enough time!

The moment the alarm rings at 6.30am, the day has begun and the race is on. All engines go.

First the derby is off to the washroom for some much needed relief and then the sprint continues to the kitchen to whip up sustenance but finish that omelette quick because the regatta is barreling down to the bus stop and now zoom to the office for meetings and an onslaught of phone interviews you lined up the night before and then a photo finish dash to the deadlines. But keep your sneakers on it’s not over yet; it’s time to Schumacher to that social life and then Usain Bolt back to bed to start all over again the next day.

San Francisco is a land of hackers. We are all familiar with the traditional ones: the computer wizards that bend technology with master strokes on their keyboards. But I have come to realize that hacking happens in more ways than one here.

Internet pioneer Philip Agre defines hacking as not just simple ones and zeros but rather “an appropriate application of ingenuity” that disrupts the daily status quo. People here don’t just hack computers. They hack time.

One of the biggest culture shocks I have experienced in bustling San Francisco, other than the weather, is how economical and wired everyone here is for minutes and seconds. It sure is a big change from the pace of reporting in Malaysia, which up until this point I thought was already breakneck. Here, every second from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. counts.

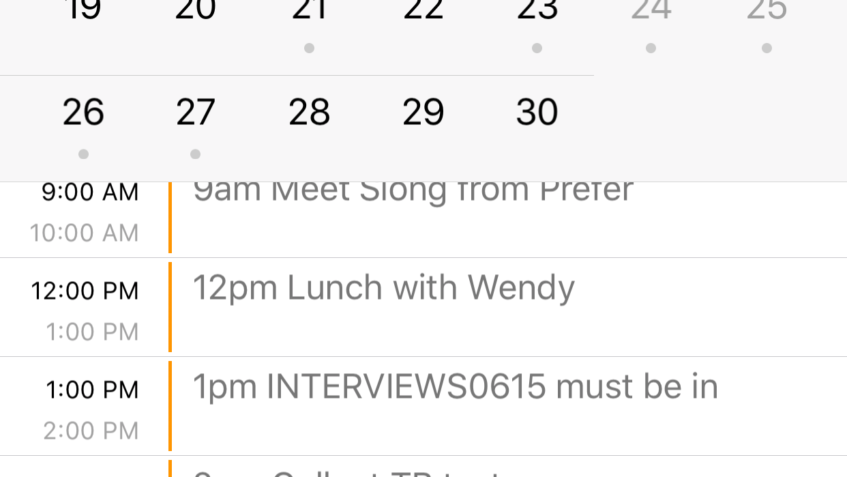

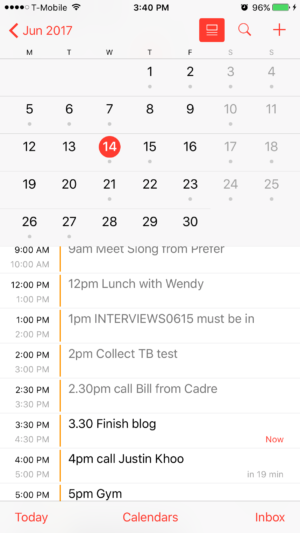

The way things work in the San Francisco Chronicle, stories are usually in by 2 p.m. even if they are assigned on the day itself . Reporters work these in with the existing interviews they scheduled days or weeks in advance. Reporters here jump from one call to the next in rapid fire succession, interviewing sources for numerous stories at one go. The editors pop in and out of meetings with photographers, graphic designers and other departments, clear stories, work reporters and speak to sources of their own.

And then there are the sources. Because I cover business, they are CEO’s, managing directors or startup founders. And it reliably takes them minutes between my first email to respond and set up an interview that is organized via email appointment and phone conference call that must end at a very specific time because they will have to hop to another meeting or interview.

No free time is left unfilled between the eight hour period for both editors, reporters and sources. If there is an email that needs to be seny, you send it now, not later. If there is a document you need to fill up, a phone call you need to make, a person you need to see — now, not later. We want to get as many stories done as we can and they want to publish as many stories as they can. In our symbiotic relationship, this dedication to time-keeping and efficiency is almost like an unspoken covenant.

A story goes from being assigned at 11 a.m., to researching, to finding sources, contacting them and making appointments in the first 30-minutes, and then getting their quotes, writing it, asking follow-up questions after editors look at it, re-writing, clearing, back reading and then it is off to the designers by 2pm.

And I’m still waiting for PR people back home in Malaysia to answer emails I sent to them in March.

If the description of how U.S. reporters work is dizzying to you, you’re not alone. I find it very difficult to jump into the fast moving stream, often feeling like a small child with arm floats, flailing in the river.

Coming from a country which has a productivity level that lags behind neighboring nations, according to analysts – this culture of time hacking can really do us some good. Malaysian working life is known for its laid-back culture, with plenty of tea breaks and office chatter peppered through the day. I wonder how much we could get done, if we all collectively decided – now, not later.