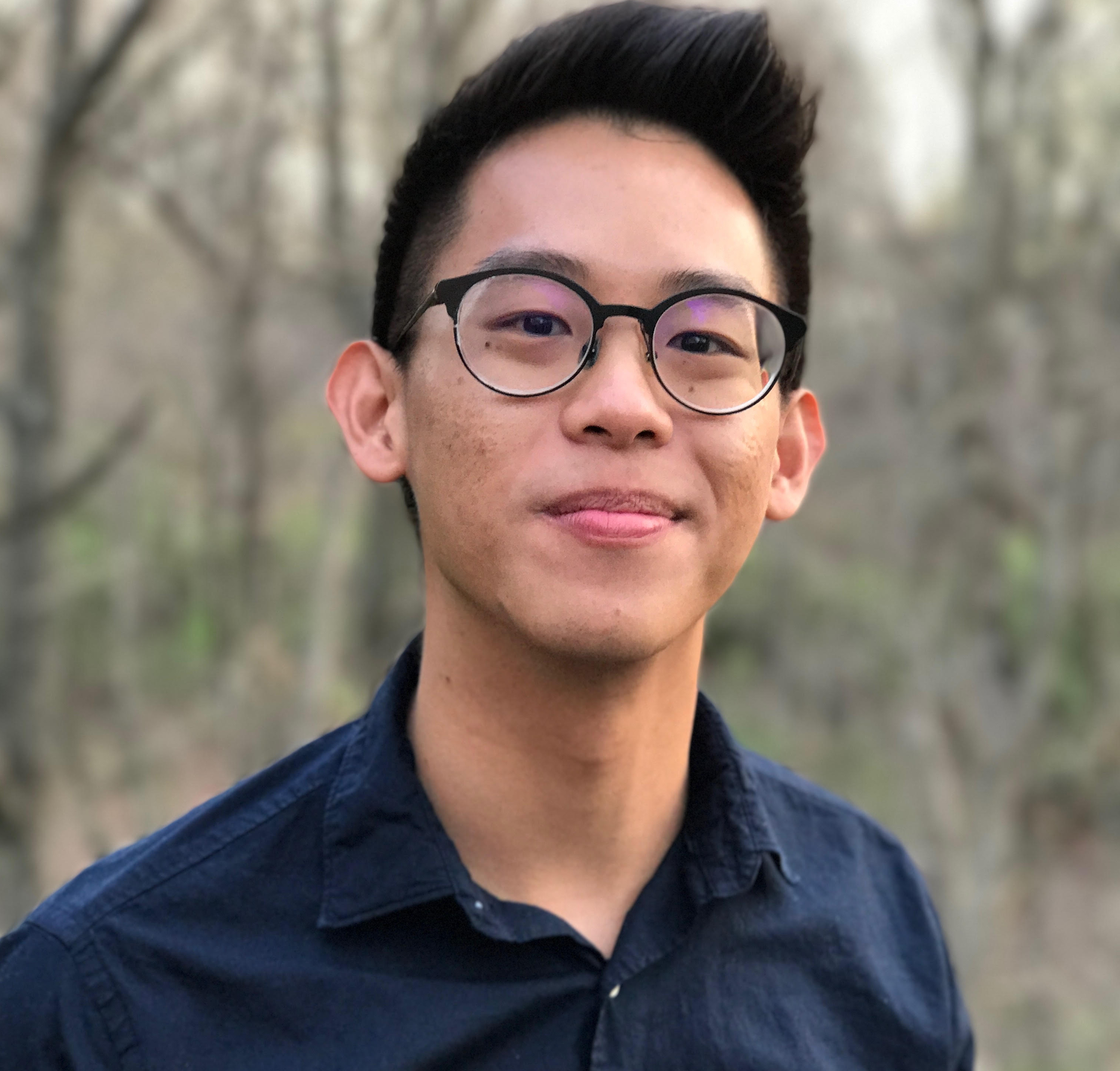

By Nicholas Cheng |

In Malaysia, some of us spend a lot of time worrying about Israel, a country 6,427 miles away, and one we’ve never had conflict with.

The last Jews left the country in the 1940’s and most Malaysians have probably never met a Jewish person. Yet the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) in a global poll ranked Malaysia as the most anti-Semitic country outside of the Middle East. It didn’t reveal how it tabulated that data, but the ADL claims 11 million out of 30 million Malaysians hold some anti-Jew sentiment and more than half of Malaysians believe Jews hold too much power in global businesses and the media.

I don’t think that most Malaysians are anti-Semitic but that poll isn’t too far from the truth.

A line that gets tossed around a lot in Malaysia is “agenda Yahudi” or Jewish agenda. A certain segment of the population, backed by Malaysian politicians and state sponsored religious authorities firmly believe that the country is under threat by Jews seeking to destabilize the country with covert, back door dealings that often involves people and organizations that are 1) against the government 2) non-Muslim and 3) are more Westernised than the usual Malaysian.

Protesters hold placards condemning Israel’s raid on a pro-Palestinian flotilla trying to break the Israeli security blockade of Gaza, June 4, 2010. Under a heavy police presence, more than 5,000 protesters, led by opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim, waved Palestinian flags and shouted “Long live Islam,” “Free Gaza” and “Done with Israel.” (photo credit: AP Photo/Mark Baker)

Malaysia is pretty tin foil hat, in that it thinks anything related to Jews or Israel is treated as a conspiracy that wants to penetrate and brainwash the Malaysian way of life, as part of some sinister Zionist crusade.

The New Straits Times, one of Malaysia’s oldest newspapers and considered a government mouthpiece, had to print an apology in 2013 after publishing a frontpage story on how opposition politicians and civil rights groups were being funded by a Jewish organization with the sole intent of overthrowing the Malaysian government. The article’s writer later admitted her story, with no sources, was fabrication. Malaysian politicians have been on record blaming Jews for political instability and economic downturns in the country.

In 1984, Malaysia halted a planned performance by the the New York Philharmonic because the show had a composition by American Jewish composer Ernest Bloch. A decade later, Liverpool cancelled a friendly match in Malaysia because the country refused to allow its Israeli player, Ronny Rosenthal, into the country. Schindler’s List, a movie about the Holocaust, was banned because the censorship board deemed it was “pro-Jewish propaganda.” Malaysia has no diplomatic relationship with Israel and the Malaysian passport bears the inscription: “This passport is valid for all countries except Israel.”

Why do Malaysians dislike Jews so much? I honestly don’t know. Malaysia, a predominantly Muslim country, has always been on the side of Palestine in the Gaza conflict. It’s something I’ve always known growing up at the height of the Oslo peace accord breakdown in the 90’s — the Jews were bad people who were killing Palestinians, people whom I personally believe have suffered just as much as any persecuted minority. I do not blame Malaysians for wanting to defend Palestine. They are brothers of the same religion and what happens to them is felt throughout the Muslim world. Imagine if Christians in the U.S. found out Christians in South Korea were being displaced from their homes and not allowed to enter their most holy places of worship. But what had always bothered me about our passion for Palestine was the equal disdain we had for the Jewish people. Why must so much love be matched with so much hate, too?

When I accepted the Daniel Pearl fellowship, I knew I was coming to the United States under the name of a Jewish reporter and that I would be working with a Jewish newspaper for a week. I felt terrible entertaining the idea of keeping my stint at the Jewish Journal in Los Angeles under wraps because being publicly associated with Jewish media doesn’t help my image in a Muslim country. But as it turns out, some of the 24 past Daniel Pearl fellows have also had the same fear —a few didn’t want their names published under articles they wrote and one refused the fellowship to avoid working there.

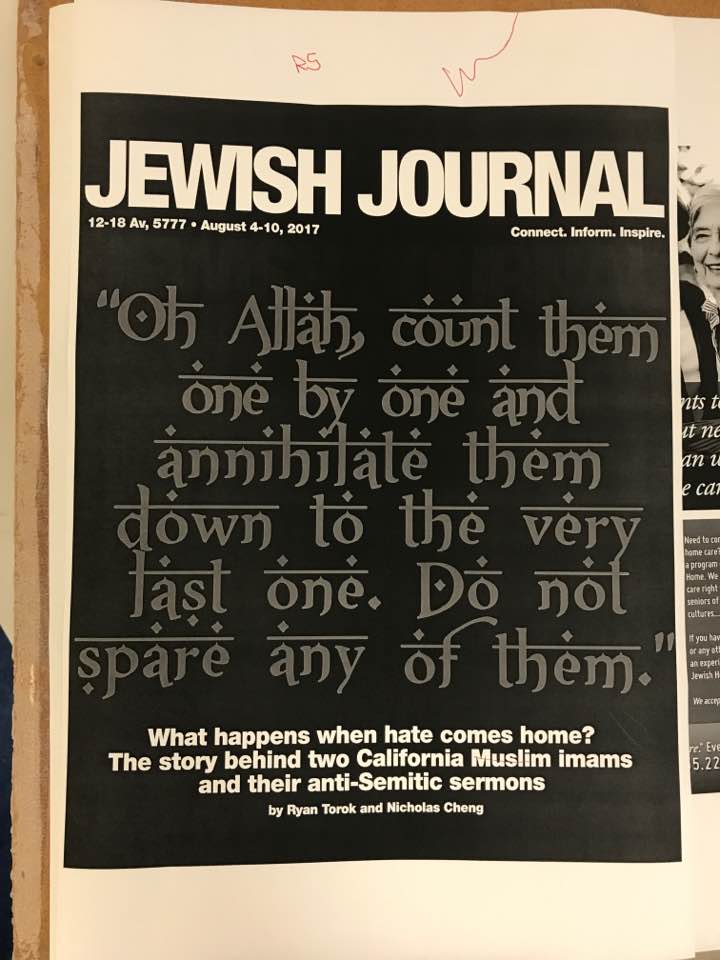

Anti-Semitic text in Arab-looking font published on the front page of the Jewish Journal spotlights the need for more understanding between both communities

My time at the Journal was incredibly pleasant. The Jewish staff members were curious to learn about Malaysia and what we thought of them. They brought me to have kosher food and attend their version of Friday prayers and Sunday mass, called shabbat. At the end of my week at the Jewish Journal I learned so much about the complexities of the American Jewish community, but I also came away just as unsettled with the whole Muslim-Jew conflict as ever.

The Journal tries its best to be the paper that strikes the middle ground between the two religions. It has a Muslim columnist, and it participates in interfaith efforts with the Southern California Islamic Center. Heck, they featured more Muslim voices than Jewish ones in a story I wrote about two Californian imams that issued anti-Semitic statements. But they also have their side. They are a Jewish newspaper after all. They speak for their community.

On my first day at the Journal, I went to a mosque to talk to people about the anti-Semitic imams. Even though they could tell I clearly wasn’t Jewish, they were afraid of me. “I know your paper; I’ve read it and..” said a woman at the Southern California Islamic Center. She chose to just smile politely than finish her sentence, but I could tell, she was speaking for her community.

It just seemed no matter how much compromise and interfaith work both sides can do, they will always exist as it is: two sides. Never able to truly be united and one of the same like the term ahli al-kitab (People of the Book).

That frustrates me as someone who is professionally, religiously and ideologically in the middle. How do you speak for two sides, who are both as well-meaning and complex and different than the other?